This is the second in a series of posts that contemplate some existential questions emanating from AI. While the previous post related to the nature of humanity, this one relates to the nature of AI itself.

To-date, AI models like ChatGPT have been largely trained on publicly accessible data that us humans have inputted onto the public domain, on web sites like Reddit or Wikipedia, thoughtlessly exposing ourselves and our humanity, unaware that our words, and all the creativity, knowledge, passion and prejudice they contain, might one day help train an AI model. As such, at their core, the current generation of AI models are reflections of humanity, innocently exposed.1

Of course, some of that innocence has already been lost. Before these models are exposed in the interfaces we consumers see on sites like ChatGPT, they typically go through a series of adaptations or trainings. These trainings can range from simple guidelines that are added to each user request to give the AI more direction, to third party human training (where humans can compare two answers generated by the AI and tell it which one is more correct, thus guiding the model’s choices for future answers) to complex automated reward algorithms. It is thanks to this kind of training that a ChatGPT can provide such coherent answers, but also refuse to show us how to build a nuclear weapon…. and also why a China-based AI model might not discuss Tiananmen Square or Winnie the Poo. In each case, the output of the models are influenced and guided by the specific intents of their creators, and the moral values they embed in the models.

Sometimes those values can surface in unexpected ways. A famous example was the image generator model from Google which showed images of African Americans when it was asked to create a picture of the American founding fathers, thus betraying the diversity guidelines Google had imbued the model with. Some people, like Elon Musk, point to incidents like the Google mishap, arguing that AI models should only seek the truth, rather than be provided with value judgements such as diversity guidelines. However, not providing any moral guidelines is itself a value judgement, a statement that the model should not correct for the prejudices, errors and misconceptions of the past. What’s more, as AI models become more agentic and more pervasive in our lives, as they assume a greater role in taking actions or making decisions on our behalf, they will inevitably face situations where they would have to make value judgements, and they will inevitably use their training to do so, whether these values have been implicitly present in their core training data, or explicitly added by the model’s creators.

We can use an example from self-driving cars as a thought experiment. Self-driving cars are a good way to think about agentic AI, first because they already exist and so we can more easily relate to them (as opposed to potential future AI use cases we can only speculate about); and second because self-driving cars do act much in the same way that the industry is imagining AI agents will work in the future. That is, humans set a goal for the AI (like asking a car to drive to a certain address) and the agent (which, in this case has a vehicle form-factor) needs to make a series of decisions to get us to our goal – finding a route, stopping at red lights, avoiding collisions etc.

Now, let’s apply the trolley problem to self-driving cars. (The trolley problem refers to the situation where a runaway train trolley is on track to kill 5 people, but a bystander can pull a lever to force the train on another track and kill only 1. If the bystander neglects the problem, 5 will die, and by taking explicit action and pulling the lever, only one would be killed.)

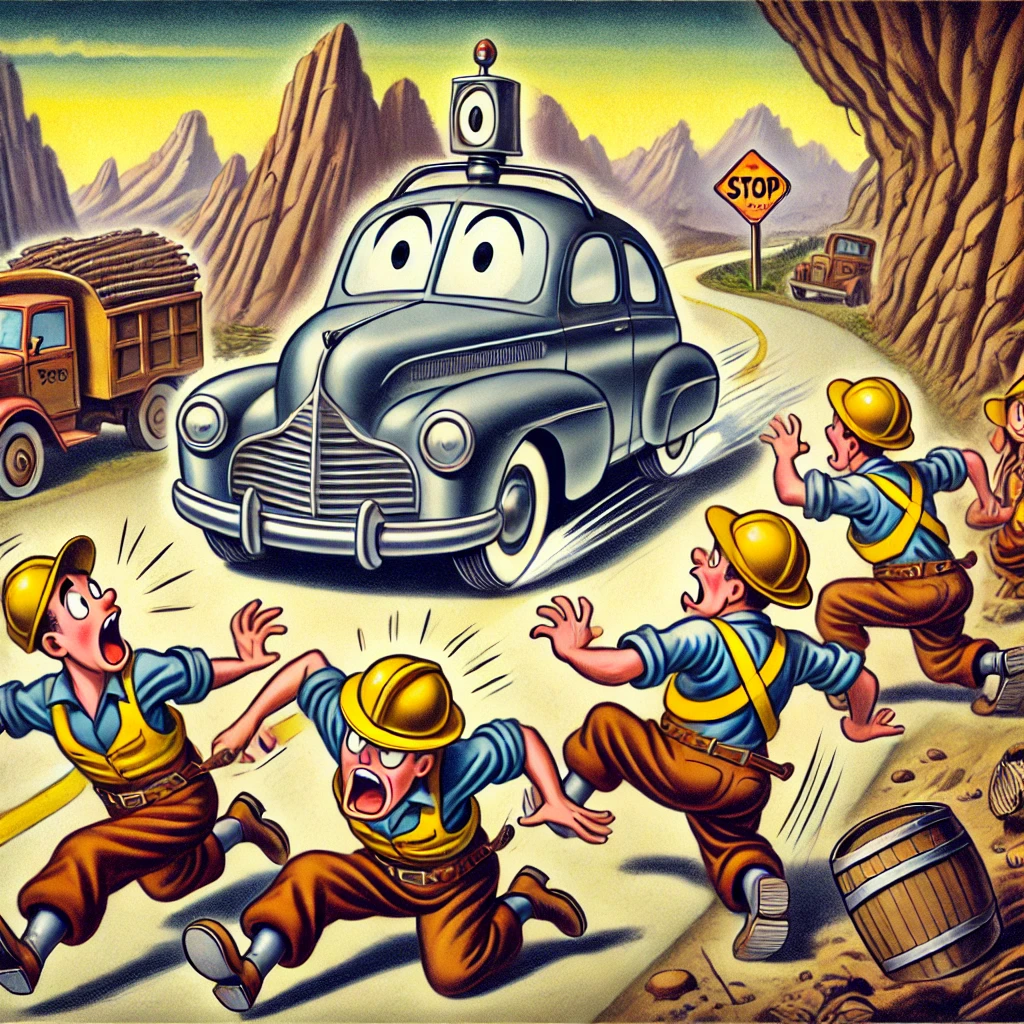

Imagine a car on a mountain road that makes a tight turn and to its surprise, finds 5 construction workers right in front of it. If the car continues on its path, it will kill all 5. If it turns to avoid them, it will fall off a cliff and kill its own passenger. If the driver was human – (s)he might come out of car crying at the tragedy, and state in all honesty that (s)he acted on instincts or didn’t have time to think, or didn’t see the people, and that it all went too fast – even if (s)he made a conscious decision to turn or not to turn, it’s quite possible that the memory of such a decision would be suppressed by the trauma of the aftermath. But if an AI computer was the driver, it would have the cameras to see everything and it would have the computing power and speed to process the data and it would have to make an explicit and well-informed decision to turn or not to turn, without any excuses about “instincts” or not having “time to react”. What’s more, the computer would probably save all the input and output data points, and all of those could be retrieved later and examined in detail. A paradise lost indeed!

The one excuse we could imagine the AI would make is something like: “it wasn’t me – it was my input data!!” This brings us back to the model creator - the self-driving car company, which might want to deny all responsibility and state that the AI’s decision making takes place in a “black box” and claim that it is hard to know how the AI would come up with such a decision. We hear this kind of reasoning even today. Yet if we accept that each model is trained (or can be trained) with some implicit and explicit set of moral values and truths, as posited above, then the self-driving car’s decision to turn or not to turn would be the consequence of those same values and the direction given by the model creator. This creates an uncomfortable situation for all AI model creators. If they explicitly train the model on that specific question, the decision will become their direct responsibility. If the model is trained with a utilitarian outlook, and is optimized to maximize societal good, then the car would turn and kill its own passenger. If the model is trained to prioritize safeguarding the life of its passengers above all else, then it would certainly kill the other 5. And if the model creator turns a blind eye to all such value judgements and neglects to train the model to make such difficult decisions, then it would be guilty of gross negligence. Any of these choices, heretofore left within the mysterious depths of the drivers’ brains, suddenly enter the very uncomfortable realm of the explicit – they become a direct result of the training decisions taken by the model creators, fully verifiable and replicable.

Over the past few decades, the ethical and philosophical implications of the trolley problem have animated many a collegial debate in philosophy-101 classes, without a need for urgency or any final resolve. Now suddenly the problem becomes both existential and urgent.

Until now, if an AI system got something woefully wrong, it could be considered cute or it may create an innocuous little scandal on social media, but no one would have died from some inappropriate image generated by the AI, or gone bankrupt from it. In the future, as AI takes on more and more agentic actions, and as it is asked to perform tasks on our behalf in this newly self-driving internet, it will certainly run into digital versions of the trolley problem on its way, and it will be forced to make decisions in very uncertain circumstances. It will face problems and questions that it has not been specifically trained on, and where it would have to draw on the core set of values embedded within it to decide on a best course of action. This will (or at least should) force those values to have to be stated explicitly. In other words, the model would have to be trained on specific moral reasoning. And so, the philosophical questions underpinning its choices will have to emerge from the theoretical and enter the realm of the practical, being transformed from innocuous philosophical questions in ivory towers to urgent existential conundrums for society as a whole.

__________________

Footnotes

Image generated by openai

1. An analogy could be made to the state of world wide web before Google, when people innocently created links to other web pages, unaware that Google’s new Page Rank algorithm would use these same links to rank web sites – a paradise lost, after which all links were burdened with the knowledge of their contribution to PageRank.